Corruption comes with substantial costs. By undermining taxpayers’ willingness to comply with the tax system and reducing the efficiency of spending programs, corruption reduces a government’s ability to efficiently deliver its policy objectives. But the indirect effects are potentially even more severe. Pervasive corruption weakens social cohesion and reduces trust in the state, which can result in economic, social, and political instability.

Amid significant macroeconomic, fiscal, and governance challenges, Sri Lanka requested the IMF to carry out a Governance Diagnostic Assessment (GDA)[1], making the country the first in Asia to participate in that exercise. The assessment is designed to assess the severity of corruption and associated governance weaknesses that give rise to corruption vulnerabilities across six core state functions[2], one of which is fiscal governance – the topic of this blog. The published GDA report identifies governance-related binding constraints on macroeconomic progress along with a set of recommendations for lasting improvement in governance and economic outcomes. The assessment drilled down on “hotspots” where governance weaknesses in PFM, tax policy, and revenue administration have created distinct corruption vulnerabilities in Sri Lanka.

On the PFM side, the GDA emphasized that the lack of a robust legal framework and transparent processes resulted in vulnerabilities in many areas. Weaknesses in budget credibility and commitment controls have led to extensive cash rationing. Poor planning and project preparation results in major problems during the implementation of many projects. Processes for approving investments and public procurement are similarly opaque, including the acceptance of unsolicited capital investment proposals, and concerns over competitiveness and integrity. State-owned entities continue to play a large role in the economy, but management and oversight are weak, with limited transparency and poor financial performance.

In the tax policy area, governance issues arose from an untransparent and complex tax system that granted wide-ranging tax concessions to selected taxpayers while imposing a high tax burden on others. Frequent tax design changes that often lacked political and technical scrutiny weighed on the certainty, efficiency, and fairness of the system, ultimately eroding tax revenue and taxpayer trust. While many aspects of the tax system have improved since the government embarked on its ambitious reform agenda, some reforms are yet not finalized. For instance, generous and long-lasting tax concessions for investments of strategic importance remain and the process of identifying such projects still lacks transparency and a rules-based character. Similarly, the Special Commodity Levy, an industrial policy tool, continues to provide uncommon levels of ministerial discretion, jeopardizing revenue collections and introducing governance vulnerabilities.

The GDA noted the absence of clear mechanisms for information sharing among authorities responsible for tax policy and revenue administration. Exposure to corruption in customs and tax administration is substantial, with inadequate means for detecting and sanctioning officials for improper behavior. Limited progress has been made in digitalizing processes for tax and customs administration, reducing the ability to identify integrity issues through data analytics. Specific issues in revenue and expenditure policies and practices are exacerbated by weaknesses in the overall systems for accountability and integrity, reducing the probability that officials will be punished for failing to comply with rules and regulations.

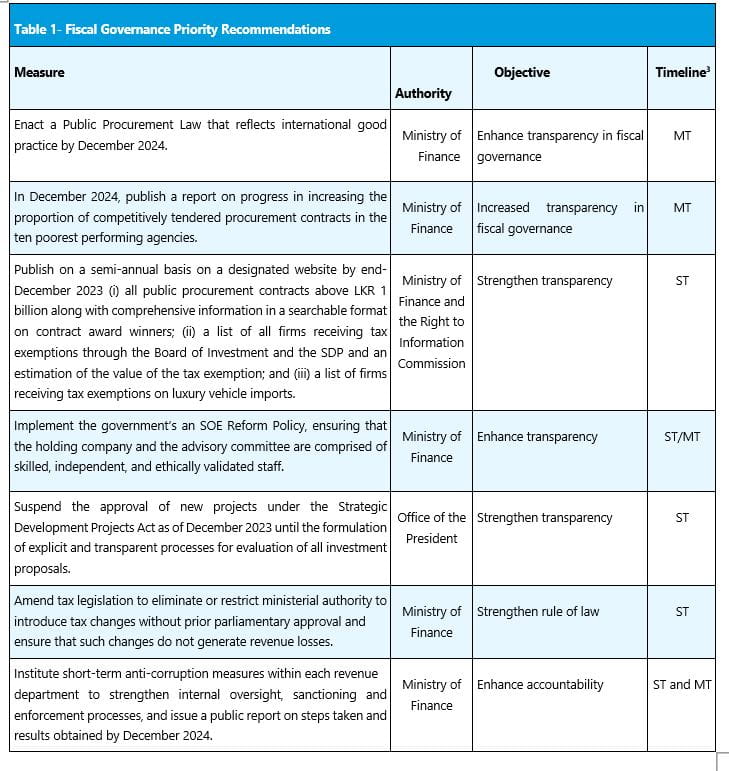

The GDA presented 16 high-priority recommendations of which seven recommendations are related to fiscal governance (see Table 1). Implementing these recommendations would require medium- and long-term efforts and significant resources, including support from Sri Lanka’s international partners.

Identifying and addressing governance and corruption vulnerabilities is essential for sustaining progress on fiscal consolidation, for supporting inclusive economic growth, and ultimately, for achieving the objectives of the government’s economic reform program supported by the IMF.

The government’s publication of the Governance Diagnostic Assessment demonstrates ownership of the report’s findings and conclusions and commitment to fighting corruption. It is an important step toward improving the efficiency of fiscal policy and toward strengthening Sri Lankan’s trust in government.

[1] The Governance Diagnostic Assessment mission was led by Mr. Joel Turkewitz (Legal Department of the IMF). The authors would like to thank Mr. Turkewitz for his leadership and contribution to this blog.

[2] The GDA examines the severity of corruption in a country, which informs the identification and analysis of governance weaknesses associated with corruption vulnerabilities across the six core state functions covered by the IMF’s 2018 Framework on Enhanced Fund Engagement on Governance: (i) fiscal governance; (ii) rule of law (contract enforcement and protection of property rights); (iii) market regulation; (iv) central bank governance and operation; (v) financial sector oversight; and (vi) AML/CFT. It also assesses the effectiveness of anti-corruption legal and institutional frameworks.

[3] The recommendations are classified as ST – Short Term to be implemented in up to 12 months from the publication of the GDA report, and MT – Medium Term that may require 13-24 months for implementation.